Parker is a Professor and founding Director of the OpenLab Collaborative Research Center at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

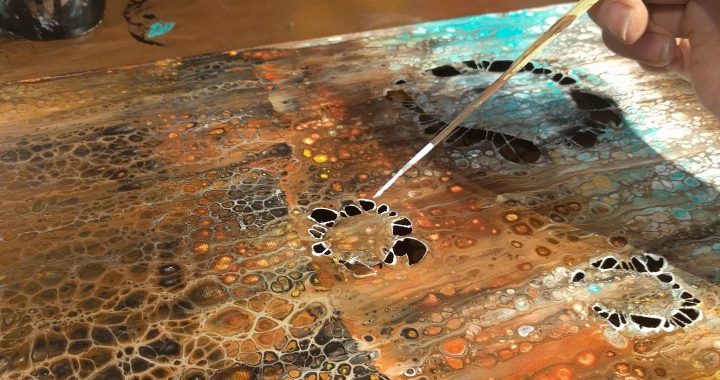

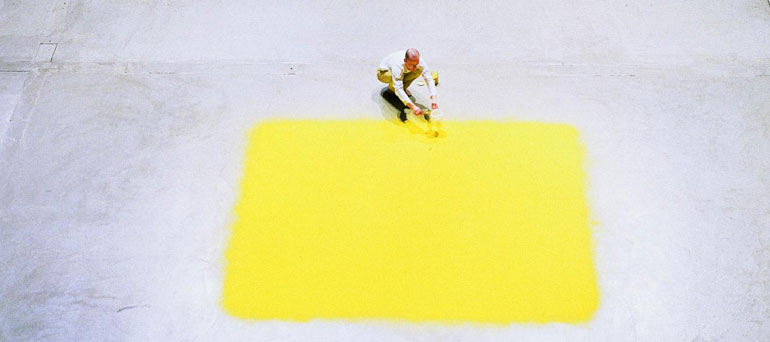

As a media artist, Parker is recognized for her innovative work investigating issues of biology and technology, combining art, ecology, and design. Through multi-sensory and interdisciplinary collaborations, she engages scientific and creative practices to explore the sensorial world of humans and the more than-human world of species living on the planet.

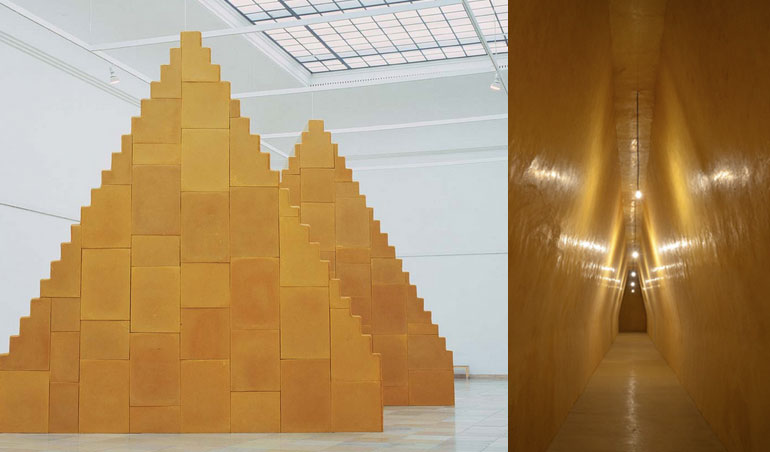

As an educator, Parker carves sites for collective engagement between disciplines. Facilitating, identifying, and determining the boundaries of complex, multi-dimensional space to develop (a sense of) community to encourage learning and inform and develop the practice of its members. Her methods of inquiry build on lab and studio visits, literature reviews, and conversations with faculty and students across disciplines, triggering a heuristic learning process to pursue creative research for exhibitions and publications.

Jennifer Parker’s website: https://www.jenniferparker.net