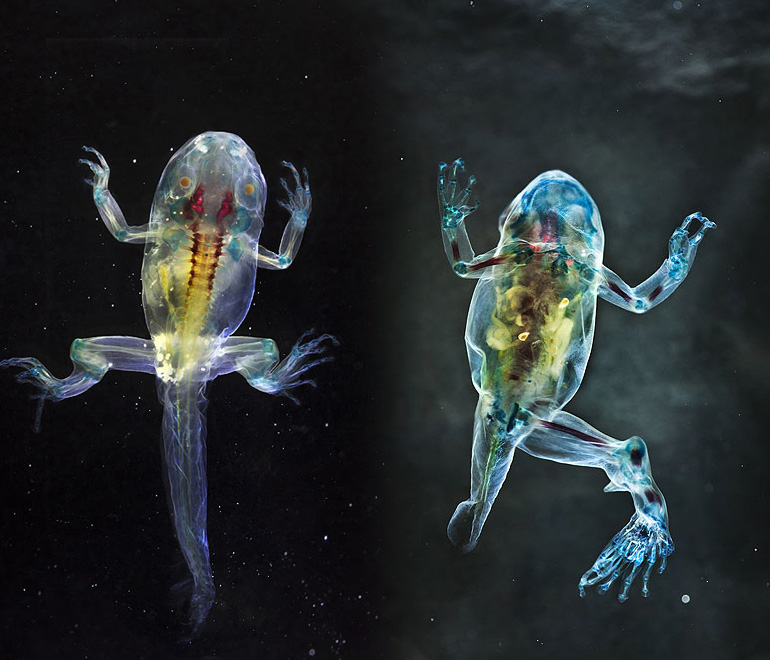

Greenberg combines art, science, and engineering to create microscopic photographs that reveal the hidden beauty of sand, flowers, food, and the human body. Greenberg builds the tools of his craft; he invented the “high-definition, three-dimensional light microscopes” with which he creates his photographs.1 His images give us unfamiliar and intimate views of materials we encounter every day.

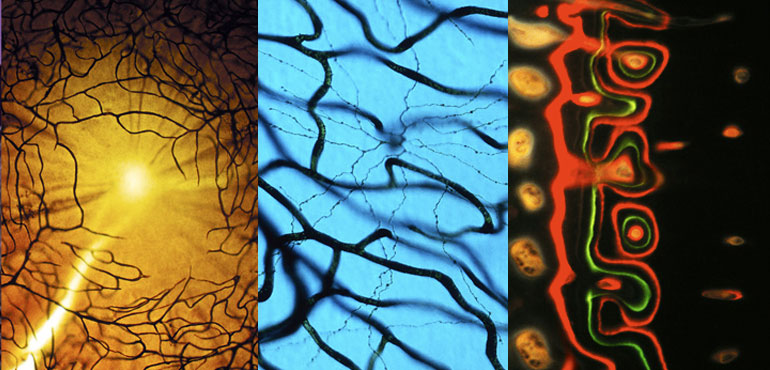

Microscopic images of retinas and bone.

Microscopic images of Royal Poinciana and Hibiscus flowers.